In today’s fast-paced news culture, misinformation and disinformation are spread with a click, often before authenticity and credibility are verified. Sometimes it's harmless and funny, like The Onion fooling Fox News. But in other cases, this type of behavior is not only irresponsible but also incredibly dangerous. To understand this culture of deception, Hopes&Fears gathered four experts on hoaxes, falsehoods, rumors and pseudoscience.

Take for instance the movement against vaccinations, which is based on research that was proven fraudulent, and has resulted in the resurgence of diseases that have been well under control for the better part of the past century. Or the Planned Parenthood controversy, in which a falsified video may lead to millions of American women losing access to the health care they can't get elsewhere. With misinformation avalanching through the internet, a hoax bust can often be too little, too late. Still, these experts work diligently to expose the truth.

SUSAN GERBIC

Co-founder of Monterey County Skeptics, founder of Skeptic Action, leader of Guerrilla Skepticism on Wikipedia (GSoW), and a regular contributor to Skepticality and Skeptical Inquirer.

BENJAMIN RADFORD

Deputy editor of Skeptical Inquirer science magazine, a Research Fellow with the non-profit Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, has written over a thousand articles on urban legends, the paranormal and media literacy.

PETER A. HANCOCK, D.SC., PH.D.

Author of Hoax Springs Eternal: The Psychology of Cognitive Deception, a book that defines and explains cognitive deception and explores its prominent potential historical instances.

GARY FINE, PH.D.

American sociologist and author, cowrote the book Whispers on the Color Line: Rumor and Race in America, areas of research involve the contemporary legend, particularly political and economic rumor.

Marcie Gainer: How do you define a hoax or rumor, and what are your particular interests in them?

Peter Hancock: A hoax, at least for my interests, is a specific belief that is related to an item or an object. In general, the nice thing about hoaxes is that they tend to revolve around a physical object or entity that you can examine. Of course, the best hoaxes have to be pretty stable or they would fall at the first hurdle. I'm principally interested in hoaxes that tend to have received quite a bit of scrutiny. They're often really well created and carefully crafted. I tend to examine the psychology behind these types of hoaxes, not only for the deception itself but also for the person who's doing the deceiving.

Susan Gerbic: A hoax involves someone who consciously tries to pull a fast one. A rumor is, to a degree, the communication of the hoax.

Peter Hancock: Right. Rumors are how hoaxes tend to propagate, how they spread from person to person, from community to community. Take for example, the concept of the “meme.” For Richard Dawkins, a meme is an idea that circulates itself in society. Of course, some of these ideas are useful and some of those ideas are clearly false. The term “rumor,” in some ways, has a negative connotation. When used, it’s often assumed that we’re dealing only with falsehoods. The interesting thing is that if we believe some idea or conviction to be beneficial, we often refer to it as “information” not “rumor.” In essence, the word “rumor” carries with it a specific connotation and that’s often a negative one.

BENJAMIN RADFORD: I should begin by noting that the popular usage of words like rumor, legend, myth, and hoax are often a bit different than how folklorists or scholars use them. For example the phrase "urban legend" is thrown around a lot to describe something that's a myth (such as that KFC uses mutant chickens in their food) or a false factoid (such as that people only use 10% of their brains), but these are not actually urban legends, which have certain characteristics including a narrative (this happened, then that happened), and usually a twist ending and an underlying moral.

A hoax is different than a rumor in several ways including that there is an explicit attempt to deceive others; sometimes it's for profit or sympathy, or to advance a social cause, or just for fun. There are dozens of types of hoaxes, from simple pranks to faked credentials to bogus Bigfoot prints to faked memoirs. Some rumors are hoaxes, but of course not all hoaxes are rumors.

GARY FINE: For me, a hoax is something that is proposed knowingly false and typically has some benefit for the creator or "perpetuator". They create these hoaxes for a substantial audience. Clearly people do these things sometimes. However I think it's fairly rare, at least in my experience, that hoaxes happen. I think what happens more often is that people begin to convince themselves that what they want to believe is what they should believe.

A rumor [on the other hand] is a statement or claim that is made without secure standards of evidence—in other words, “How do you know?” It's a question that philosophers refer to as Epistemology. How do you know what is true? When someone makes a statement, is it right or is it not? We judge this on the basis of two components—first, The Politics of Plausibility, where we ask, "Do I see this rumor or statement as plausible?" And second, The Politics of Credibility, where I decide in the source of the information, in my judgment, is credible.

Marcie: Where does pseudoscience fall on the spectrum?

SB: Pseudoscience lies outside of science. Usually, believers don't know it's nonsense.

PH: Well, pseudoscience is a pursuit which uses, or ostensibly uses, the methods of science. But in reality it abuses the methods of science. It sort of fakes the process, or rather, doesn't adhere to the process. Essentially pseudoscience doesn't play by the rules.

BR: It often uses words such as "quantum" or "vibrations" and symbols like lab coats or beakers that the public associated with science to give a discredited or unproven idea the veneer or appearance of scientific legitimacy. Astrology, homeopathy, and reflexology are examples of pseudoscience.

GF: I kind of want to turn this on its head. I would emphasize, and it’s not necessarily what the other experts will emphasize, that we should be very cautious of saying there is "science" and "pseudoscience." This distinction echoes the idea that we can actually determine what is what. To speak of "pseudoscience" is to define “science” as constituting of a group of elites. But elites, as in politics as in economics, are not always right. They're not always wrong. They may be more right than wrong. I am not arguing for throwing out elite judgment. But we should be cautious about it and in turn be cautious about using “pseudoscience.”

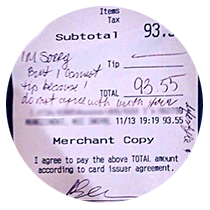

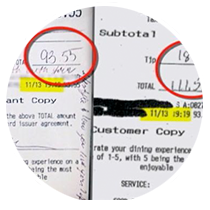

NOVEMBER 13, 2013: A waitress named Dayna Morales posts a story on Facebook claiming that a family had refused to tip her because she was gay. She writes that the family insults her and includes a photo of a restaurant check with a note reading "Sorry I cannot tip because I do not agree with your lifestyle & the way you live your life."

NOVEMBER 14: The story is picked up by local and national news outlets and immediately goes viral. Morales appears on a number of broadcasts to discuss the incident. People show support by donating tips to Morales, and her employer sets up a PayPal in her name.

NOVEMBER 18: Morales announces that she has received over $2k in donations and that she will donate them to the Wounded Warriors Project. Commenters note that her decision to not keep the money further verifies her original accusation.

NOVEMBER 25: The family accused of stiffing Morales contacts the press saying that a copy of their receipt is being used as a hoax and provide a matching receipt and Visa bill that shows that they left an $18 tip. They go on to note that they specifically didn't vote for a local governor because he did not support gay marriage.

NOVEMBER 27: Ex-friends and co-workers begin contacting the media saying that Morales had lied about incurable brain cancer, being the sole survivor of an attack while serving as a Marine in Afghanistan, and more. Morales' ex-girlfriend also notes that the handwriting on the original receipt looks like hers. Morales goes silent.

DECEMBER 5: A local Patch investigation reaches out to the Wounded Warriors Project, which says it hasn't received any of the promised donations. The restaurant conducts an internal investigation and suspends Morales.

DECEMBER 7: The restaurant releases a statement that they have fired Morales and that donations will be refunded.

Marcie: Why would someone go out of their way to create an elaborate hoax? What do they hope to get out of it?

BR: There are so many different types and the motivation for each kind is slightly different. Money is a big one. For example, James Frey wrote A Million Little Pieces and lied about its authenticity to sell copies. He believed if he presented this fictional story as his real life experience that people would find it all the more powerful, motivational, and inspirational, so he faked it. But if someone is faking an illness, a lot of research done by the American Psychological Association finds that the motivation isn't money, but the desire for attention and sympathy.

A lot of times what happens is that a hoax begins as a little white lie. In case after case I've researched, many of them start small and then snowball. In order to keep up the lie you have to keep lying. It builds and builds and builds until eventually it becomes a huge lie. This is especially true with the catfishing hoaxes. People always say, “Didn't they realize they would be discovered?” Well, they weren't thinking about being discovered. When we see catfishing presented in the media, it’s shown as this huge, intricate scheme. But for the catfisher, it happens slowly—one little thing at a time, one email at a time, one faked photo at a time.

PH: I think in general the foundation can be traced back to Nietzsche and the "Will to Power." What you find is that there's a benefit for the catfisher/hoaxer in there somewhere. According to G. Gordon Liddy, one of the men involved in Watergate, we should always “follow the money." Quite often that's a pretty easy motivation to spot in our society because we're very money-oriented. Or a catfisher may get some satisfaction by feeling as if they’re better than the person they duped because they fooled them. There are a lot of potential reinforcements, but they all boil down to expressions of the “Will to Power." There’s an instinctual need to have influence over other people in some fashion or another.

SG: People who create hoaxes, catfish, or spread rumors may just think they are clever trying to pull something over on others. I assume that is what it is. But it’s possible that they really are trying to help others by embellishing something they heard and thus trying to make others safer. For instance, People are afraid of gangs shooting and killing their kids. So they may tell their kids (the ones that drive) not to flash their headlights at an approaching car that has its lights off, because they’ve heard this could be a gang initiation in which that oncoming car could run you off the road and shoot you. Also, urban legends give security to people living in a confusing world. So when I tell my kid not to flash his lights, Suddenly I don’t have to worry as much about my kids driving around. I know it may sound silly, but these people now feel like that they have some control.

Marcie: Can you explain your process for deconstructing a hoax or a rumor?

PH: It’s best to begin by looking at the various levels of the claim. For example, when dealing with accident reconstruction, start by establishing as much of the factual basis as you can. In the areas of deception, the “social utility” of the claim or story comes into play. People will willingly believe falsehoods or bad information for all sorts of reasons. To illustrate “social utility,” we can look at specific events in history where society “constructed” a hero narrative. For instance, Custer's Last Stand was a bit of a debacle, but the pervasive social narrative of the “Great American Story” conformed Custer into a hero-figure. Even though accounts might not always accord exactly with what reality was, they can sometimes have a social function as well. In short, you have to look at evidence on several levels. If you just look at things on one level, it’s easy to miss the big picture.

SG: Well, when we approach a Wikipedia page that doesn’t use critical thinking, we start looking for great citations on the Internet. When it comes to the paranormal, we will often find the citations with people like Ben Radford and friends. We have rewritten many paranormal pages on Wikipedia. Just last night I rewrote the Bell Witch page, using articles that Radford, Brian Dunning and Joe Nickell had written as sources. If I’m examining just a generic hoax or rumor that is floating around Facebook, I usually first check Snopes.

BR: Unfortunately I, just like Snopes, can't be everywhere all the time. I'm not scouring the internet every waking moment to see what new rumor or hoax is bouncing around. Typically what happens is somebody will contact me with a particular hoax or story they think is dubious. If I have time, I'll look into it. First, I identify the sources. Who's saying this and why? Sometimes these rumors can be quickly debunked if you find out the story is from a satirical website. Because some of these sites look very realistic and authentic, their stories can quickly spread around. Second, I identify the variants. "Variant" is a folklore term meaning there are different versions of a story that circulate in different areas. For example, if there's an internet hoax flying around about a particular topic, I will often try and seek out a half dozen or so different news stories on the same topic. Often, the multiple stories will contain different information, such as an added detail or an “according to Person X” anecdote. Sometimes they'll just be cut and paste versions of each other.

Then I cross-check the sources. I’ll say, "Okay, this person is attributing this to a researcher in England, Dr. Bob Clark of the University of Hertfordshire." Is there a Dr. Bob Clark at the University of Hertfordshire? This can be determined fairly quickly through an internet search. But if you can’t verify his existence at the University, it doesn't necessarily mean it's a hoax. Your internet searching could be wrong. It could be Dr. Bob Clark is a new staff member. That by itself doesn't mean the source is definitively bunk. It just means you have one more red flag. So, basically, the process I have of investigating these hoaxes and internet rumors is a process of collecting and counting red flags. If I get to three or four or five red flags, I'm pretty sure I’m dealing with a hoax.

Deconstructing the Planned Parenthood scandal hoax

PUT CLAIMS INTO CONTEXT:

1. A secretly-recorded video is released by Center for Medical Progress, an anti-choice organization that set up a fake biomedical research company to acquire credentials necessary to enter classified talks with Planned Parenthood.

2. It is revealed that the video is highly edited to frame Planned Parenthood as profiting from the sale of tissue from aborted fetuses.

CONDUCT INVESTIGATIONS:

3. Planned Parenthood hires Fusion GPS, a Washington-based research and corporate intelligence company to investigate the videos. They find that the videos were altered.

4. FactCheck.org speaks to experts about the possibility of profiting from fetal tissue sales at the prices mentioned in the video. Experts agree that the prices are far too low for profit and just cover operational costs of providing tissue for research.

5. Probes by multiple states sparked by the video find Planned Parenthood within full compliance of local laws and regulations.

REFUTE CLAIMS USING EVIDENCE AND GO ON THE COUNTEROFFENSIVE

6. Planned Parenthood releases a statement explaining legal and ethical guidelines for tissue donations and its compliance with such.

7. Cecil Richards, President of Planned Parenthood, provides the US Congress with an analysis of an internal review of practices, outlining the fraud committed by the Center of Medical Progress and the federal and local laws broken by the group, and highlighting a 1993 bipartisan US law promoting fetal tissue research.

Marcie: Let’s discuss the recent Planned Parenthood hoax, in which anti-abortion activists framed the organization on video so that it appeared to sell body parts from aborted fetuses for profit. Now the US House of Representatives has voted to defund Planned Parenthood, even though the video was grossly misleading. What is the best course of action to undo the damage done by a hoax like this?

SG: Do what they have been doing. Come right out and get the message out that this was a planned takedown of their company. Expose who the accusers are and stand firm. Make sure that their house is in order too. They may have been at fault in some way and they need to learn what went wrong and how to fix that. As a skeptic working to educate, I would then find sources that show who really was responsible and make sure those get on the Wikipedia page. Anyone who Googles Planned Parenthood is most likely to get a link to Wikipedia almost first.

PH: Keep hammering away at the truth. For Planned Parenthood, it would be to put the information out there, tell people this is where the information is, let them look, let them make judgments for themselves. This case is a classic example of people selecting and picking certain information to use it how they want while just ignoring the rest. At the same time, what you've got to do is understand why the person said what they did about you. What was their motivation for misrepresenting? What you do is you turn the mirror of truth back onto somebody else.

BR: There are a couple of things that can be done. First, Put the claims in context. Basically, when these types of damaging rumors come up, the organization can say something like: "Look, this is not the first time these people have faked evidence trying to implicate us. This is par for the course. We're Planned Parenthood. There are anti-abortion activists who've hated us for decades. They've tried stunts like this before.” Then, conduct independent investigations. In the Planned Parenthood case, there were three or four investigations that determined there was no wrongdoing. The next step is to refute the broken law claims of selling fetal tissue, with the findings of the independent investigations. "Look, these people looked into this. This is their conclusion. We did nothing wrong."

Finally, go on the counteroffensive. Say, "Look, you the public should ask yourself why these people are manufacturing damaging evidence against us. If we were really doing something wrong, why not go after that? Why do they have to make these stories up?" Put the seed in people's minds that maybe the accusers have their own agenda, which they clearly do, and that's tainting their position. I'm not a reputation management agency or PR people although, I probably should be if anyone wants to contact me, I'm looking for work! [laughs]

GF: I teach a course on scandal, and to me, the Planned Parenthood video is a precise example of what a scandal is. A scandal is not necessarily a crime. It's not necessarily about something that is illegal. A scandal is when something that, within a community, is taken for granted is then exposed to another community that is unaware of how things operate. The Planned Parenthood video represents that precisely.

What happened is that the Planned Parenthood employees understand that that's how things work: okay, they're having lunch and a glass of wine and a salad and they’re talking about abortions and, you know, that's kind of normal life for a Planned Parenthood employee. But when people who don't know how that world operates discovers it, people may become bewildered: "You're talking about abortions and sipping chardonnay?!" It may be seen as disgusting or disrespectful. Essentially when a certain group suddenly discovered that these issues were discussed so casually, it seems scandalous.

Marcie: Another big misinformation rumor is the idea that vaccinations cause autism. In his 1998 research paper, Dr. Andrew Wakefield claimed that the MMR vaccine was linked to autism—a fraudulent assertion that has since been debunked by other scientists. Yet the anti-vaxxer community remains as strong as ever. Why do the anti-vaccine communities continue to adhere to the rhetoric of vaccine dangers?

PH: Well you get into the proximity question, which is that people often confuse correlation and causation. With some of these vaccines—I'm not going to speak to all of them, because I don't know all of them—the onset of a problem occurs at a certain stage of development about the same time the vaccination is being given. They see a correlation between the vaccine being administered and the problem arising and misperceive it as causation.

BR: There are a couple of reasons why the anti-vaxxers’ positions and beliefs are so intractable in the face of evidence and arguments. For starters, there's a very strong conspiracy theory element to it and conspiracies are very, very difficult to disprove. One of the things that comes up is the distrust of government and Big Pharma. This assumption that the dangerous risks of vaccines are being intentionally hidden from the public by doctors and drug companies often claiming collusion with the U.S. government for big profits. Because of the conspiratorial nature of this belief, any evidence you offer is assumed to be part of the conspiracy. If you point out to people, and I've done this, that Andrew Wakefield's paper was retracted, their answer is, “Well that's because the AMA and the British Medical Journal are trying to silence him.”

Also, humans are story-loving creatures. Even though in science anecdotes aren't evidence, personal anecdotes can be more powerful than science. So when you hear, for example, Jenny McCarthy on television crying about her child who she believes has advanced autism or other medical problems because of vaccines, that's very powerful. She genuinely believes this, which makes people believe it, too.

Marcie: So how do you convince someone with such a steadfast belief, like an anti-vaxxer, to acknowledge the truth?

BR: Offer alternative explanations, respectfully. When dealing with people the least effective thing to do is to insult their beliefs.

SG: Right. Someone attacked their beliefs and they circled the connotative dissonance wagons and doubled down on their beliefs. I’d start by pointing out a few facts—after doing my thing and checking to make sure the Wikipedia page is in great shape, because I know that they will eventually find their way there and I need to know that they are getting great information and citations.

Then you need to decide if their belief is harmful. Is it harmful right now or harmful in the long term? If it is just some silly belief like aliens helped build the pyramids, then yeah that is stupid, but it isn't harmful right now. I would tell them that I watched a documentary about how men worked for years with large logs and rolled the stones into place. They had skilled people working on the pyramids. I would not call my friend an idiot, I would just let them know that there might be another explanation. Nothing confrontational. You have to allow them to save face, otherwise they will never hear what you have to say. If it was harmful, like someone going to the Burzynski clinic for cancer treatment, then I would need to intervene with information—again making sure the Wikipedia page is in great shape.

PH: There's a well-known quotation: "For people who disbelieve, no proof is possible. For those people who believe, no proof is necessary." So in these situations, we're really looking for a middle ground. Most people can be persuaded one way or another, so I think you have to keep hammering home the issue of the facts and the data. In the end those who are willing to pursue it long enough, will actually find out what that current state of knowledge is. Of course, we don't know everything, and that's one of the big problems. Even in science. Like in the Piltdown Man [hoax]; what was accepted as fact at one time is not always going to be stable.

I did actually coin a phrase that got picked up by some people, which is "Know Doubt." You have to keep doubting things, even your own beliefs. I think we really have to keep our greatest skepticism for some of our strongest beliefs. Even scientists, as the Piltdown event shows, can fall into those same traps. It's a matter of constantly questioning.

Marcie: Was there ever a hoax or rumor that was incredibly hard to debunk?

SG: I've been involved in so many of these I can't think of one that I could not handle pretty easily. Maybe climate change? I don't have a science background and that is something a lot harder to deal with. Maybe GMOs. Those are more recent and I'm not as experienced with them.

GF: Oh, there's lots that we can't verify or determine whether it's false or true. Can I say that a rat was, at some point in history, found in a bucket of fried chicken? No, I can't say for sure. One of the rumors that we talk about in Rumors on the Color Line is the CIA bringing drugs into African American communities. There's no convincing, firm, secure evidence for this. But can I say that it didn’t happen? No. Essentially, there are a lot of rumors that we shouldn't take seriously until proven.

BR: Some of the research I do, in terms of folklore, is... it's frustrating. You just resign yourself to the fact you may not get an answer. For example, I did an investigation article on the urban legend about kidney theft in Latin America. I was trying to figure out who started these rumors and legends. I spent a lot of time, interviewed lots of interesting people, and I have some progress on it, but ... there's no way to know exactly. It's impossible to debunk these things. They keep coming up.

Marcie: Do you think the internet fuels rumors because they can spread further faster, or does it actually help extinguish them because of the availability of resources like Snopes and FactCheck.org?

GF: What the internet does is allow rumors to spread very rapidly. But it also allows rumors to collapse very rapidly. Pre-internet, we would see this slow upturn of information. Information was spread person to person, sometimes through various newspapers, and so forth. It would reach a peak and then it would begin to decline. This might even be a multi-year process. In the Internet age, for particularly potent rumors, they may spread widely within a day, a week, a month. Then if the rumors are not seen as plausible and the sources are not credible, they disappear quickly. The correcting occurs just as quickly as the original spread.

BR: Obviously the internet has been an incredible resource over the past two decades in terms of the amount of information available. It's amazing. how anyone with an internet connection has access to an unimaginable amount of information on Wikipedia and elsewhere. In some ways, the internet is an amazing spectacular step forward for humanity, humankind, and human knowledge. Hand in hand with that, of course, is disinformation. And misinformation. And, as in the days before the internet, they'll always be a step ahead of the truth. The ultimate problem is a journalistic problem. It's also a human psychological problem in that the sensational, flashy headlines are going to make the news. The eventual debunking, if indeed that happens, always comes later because it takes time for somebody to research it. The follow-ups and debunks are never interesting and never circulate nearly as much as the original story. That's just the nature of news and it's unfortunate.

PH: The problem is that a lot of misinformation can get ported from one website to the next. You can then see two or three websites that say the same thing and turn around and go "well that must be right," without realizing that they have a common source. There's an issue here: the cost of information. It's sort of the degree to which people don't want to expend too much cognitive effort on something because it actually costs a lot of energy to sit and think about things, so sometimes it's a lot easier to believe the surface information that you receive very easily that's said to you rather than spending a lot of time and effort to find out whether it's exactly right or not.

BR: I actually try to fight that when I can in my articles and columns for The Skeptical Inquirer and elsewhere. I see a lot of value in follow-ups. I can't always do it, but I do make an effort to find stories either I reported on or someone else reported on and bring them back up. "Remember this story? What about it? Was it really true?"

PH: For years I've been subscribed to and had work published in The Skeptical Inquirer, but you know it always seems that the avalanche, the tide of misinformation just keeps coming and coming. In the end, I know that some people just sort of give up like it's always going to be like that.

Marcie: Can a hoax or rumor ever be beneficial?

PH: Well I suppose they can be used for ends that are generally socially beneficial. But when people inevitably find out that they’ve been duped, there will usually be a pretty strong backlash. This will then have an effect on any other type of information coming from that source or discipline. For example, you could communicate that vaccinations are a good thing, but you might have the wrong evidence for why this is so. You spread this information with the good intention of bettering public health, but once people find out that your claims were based on falsehoods, they will then look very skeptically at the next claim about advancing public health issues. I think you have to try to be as truthful as you can.

GF: Rumors occur when there is insufficient information to public demand. And so they reflect the concerns of society. In our book Whispers on the Color Line, Patricia Turner and I talk about rumors as being like a canary in a coal mine. They provide us with a sense of what people are concerned about — what they believe. What they feel is plausible and who they believe is credible.

BR: My answer would be no. I, personally, don't think there's a greater social good to a hoax simply because it is misinformation. If you act on misinformation, you could start a war. You could wrongly finger some poor guy as the Boston Bomber, or your children could get polio. There are very real consequences to this. I can't think, off the top of my head, of any cases in which acting on misinformation helps anybody. Personally, I spenD so much of my time trying to separate truth from fiction, from myth, that I, to be honest, find it offensive when people intentionally blur the lines.

Originally published on Hopes&Fears (no longer publishing).

Editor: Gabriella Garcia

Illustrator: Jasu Hu